A consumer phenomenology of the digital

Somewhere in Plato's work you'll find an argument against writing. That's right; writing, as such. Given how important writing is to me, it always gives me an unsettled feeling to consider whether Plato is anywhere near worth taking seriously on this point.

In the Phaedrus, Plato makes Socrates say that the written word will degrade human memory and remove the dialogic character of thinking---a text may speak to you, but it never listens. This moved humanity away from a rich oral culture of conversation, story-telling, and discussion towards a solitary culture of rigidity and bookishness. Socrates makes it seem that the invention of writing was not human progress at all, but a form of destruction.

I don't think Plato---who was a writer---means this to be his final verdict, given the many benefits writing brings to people. But in a series of recent books the philosopher Byung-Chul Han has revived this type of reactionary argument. This time the new invention is that of digital communication and digital media. According to Han, they undermine community, stamp out attention and ritual, and lead to a culture of narcissism.

Also this argument leaves me feeling unsettled. Let me be clear from the outset, I disagree with Han. But I would not talk about it if there wasn't was something to learn from his work.

Reprogrammed by a new medium

Digital technologies, like writing and the printing press before them, are changing dramatically the ways humans live. That seems incontestable. But Han does not like what he sees. As he opens his book In the Swarm:

In view of the meteoric rise of electrical media, Marshall McLuhan observed in 1964: 'The electric technology is within the gates, and we are numb, deaf, blind, and mute about its encounter with the Gutenberg technology.' Matters stand much the same today with regard to digital media. This new medium is reprogramming us, yet we fail to grasp the radical paradigm shift that is underway. (In the Swarm, p. ix)

What is wrong with humanity's adoption of digital technology? Han's brief answer is that it reduces human society and life to a faint shadow. Digital media ruin community and isolate human beings. If people communicate digitally, then this does not establish relationships, it will be disembodied, and leaves no room for shared feelings. Digital communication is predominantly affect based (which Han links to narcissism) and it develops into a form of communication without community.[^1]

This suggests that instead of being just an ambivalent cultural phenomenon, the move to digital tech marks our downfall as human beings. A significant current within Han's work of the last seven years or so propels this diatribe against digital technology.

A bland mix of truth and nonsense

These are bold claims and, frankly, I don't think Han explains why anyone should believe them. His writings are rather sparse on argumentation and the most striking assertions are made without giving a reason. This is no accident or oversight. His books engage readers at a more holistic level. They offer something like a compelling picture of how things really are---a strategy Wittgenstein at some point preferred as well. It means sketching a portrait of forms of life that a reader will immediately recognise but nonetheless casts in a new light: 'Yes, that's it! That's my predicament!'

This sort of picture-writing runs the risk of allowing valuable truths to combine almost imperceptibly with exaggeration and nonsense. The resulting mixture may appear plausible, but would be dangerous to embrace uncritically. The following passage from one of Han's books may serve as an illustrative example:

Symbolic perception is gradually being replaced by a serial perception that is incapable of producing the experience of duration. Serial perception, the constant registering of the new, does not linger. Rather, it rushes from one piece of information to the next, from one experience to the next, from one sensation to the next, without ever coming to closure. Watching film series is so popular today because they conform to the habit of serial perception. At the level of media consumption, this habit leads to binge watching, to comatose viewing. While symbolic perception is intensive, serial perception is extensive. Because of its extensiveness, serial perception is characterized by shallow attention. Intensity is giving way everywhere to extensity. Digital communication is extensive communication; it does not establish relationships, only connections. (The disappearance of rituals, p. 7)

Now this feels somehow explanatory, doesn't it? But on a closer look it reveals itself to be no more than a succession of more or less recognisable ideas. True, it is a documented fact that attention span has fallen below historical norms. And this may be associated with what Han calls 'serial perception', a form of experience that rushes from one piece of information to the next. But why would an attention deficit lead to binge watching? Wouldn't someone with shallow attention precisely hop from one activity to another, instead of staying focused on episode after episode on Netflix? We don't get the reason. The next stop is the assertion that serial perception is 'extensive'. We are not told what this means, but let's assume this is so. Then does it then follow that digital communication is extensive as well? That it does not establish relationships? The logical connections are missing and no reasons are given. All we get is a provocative idea to take home: digital communication does not establish relationships.

Life in a digital panopticon

You may think I'm being pedantic. As I said, Han's books don't seem intended to be read in this analytic way. In fact, they resemble very much the hasty and affective form of communication that Han is criticising. His staccato chapters try through repetitive proclamations to stir up a sense of recognition in the easily distracted reader of the twenty-first century: "Yes, this is what I see around me!" And then, after having embraced them, Han's words might summon a certain degree of outrage: "No, he's right! We cannot continue to let our lives be hollowed out by this digital paradigm!"

To have this reaction to our current predicament would not be misplaced, and to that extent the texts do their work. The image of society that emerges from Han's work is both recognisable and it is alarming. It shows us as living in a world that is becoming increasingly egocentric and more and more anti-social. Han is one of several authors writing about the way neoliberalist societies cultivate egoism and narcissism.

When he goes online Han sees a 'digital panopticon', a virtual world in which large numbers of people are performing the unpaid work of tweeting, vlogging, and linking in a hyper-surveillance economy. It's a system that tricks them into thinking they are free (they can share what they want, right?). But in fact they are the serfs that secure the platform's profit. As Han puts it:

In the digital version of the panopticon, we are not simply imprisoned. Rather, we are active participants. We take part in building the digital panopticon. By exposing ourselves, by hooking ourselves up and voluntarily uploading our body-related data to the net, like the millions of devotees of the ‘quantified self’ movement, we actually maintain the digital panopticon. (Capitalism and the Death Drive, p. 25)

This socio-economic system we increasingly inhabit is a 'digital feudalism', about which Han says:

The digital feudal lords, like Facebook, give us some land and say: ‘You can have it for free. Cultivate it.’ And we cultivate it exhaustively. At the end of it all, our feudal lords return for the harvest. This is a surveillance and exploitation of all communication. The system is extremely efficient. No one protests against it, because the system exploits freedom itself. (p. 89)

This seems apt, and it puts a finger on the way neoliberal capitalism uses digital technology against people, to exploit people, and, as Jodi Dean recently put it, to protect the rich and powerful from the rest of us.

The click of a button?

As so often, it is neoliberalist capitalism that's ruining the good life. In many places Han does identify this neoliberalist crusade for individuality, increased productivity, and surveillance as the culprit of our disintegrating sociability. Yet there are almost equally many places where Han blames digital technology and digital communication for having caused those things. Han's critique of neoliberalism seems inseparably fused to the critique of the digital. Neoliberalism and digital technology, they would seem to be two sides of the same medal.

Although this once more seems a provocative idea, I don't think it is right. I think it is rooted in a distorted image of tech.[^2] In an interview, published as part of his book Capitalism and the Death Drive, Han says that "the digital as such pushes us towards transparency. When I push a button on the computer I immediately get a result". Observations of this sort recur in his work, that digital technology makes everything transparent, facile, and impersonal. And such observations are revealing.

They are revealing, because anyone who has tried to get digital technology to do things that bypass or subvert capitalist intentions will know that what Han says is false. Just try to set up a free and open social network for friends or comrades, or try to programme home appliances that do not spy on you. Those things won't go with a click of a button. Quite the opposite. If computers always gave immediate results, there would be no Stack Overflow, and no sprawling community of hobbyists, FOSS-activists, and hackers.

Han's misdirected aversion to digital technology is perhaps understandable, and may be a sign of a general problem. The image of digital technology has become warped under the influence of neoliberalism. And this is not by accident. If the only things that come to mind when you think of digital communication are Facebook, Twitter, and Tiktok, then it may be hard to discern the true potential of online communication. And that serves some people all too well.

A gap between cultures

In his book Exponential (2021) Azeem Azhar describes an increasing distance between those that primarily know digital technology as it is made available to them as consumers, and those that have knowledge of the hardware, source code, and network protocols. Building on a notorious lecture the scientist and novelist C.P. Snow gave in 1959, Azhar describes ours as a society of two cultures. It is the programmers, engineers, and hackers that know what digital technology is and can do. Its users often show a fundamental ignorance. "Effective analysis of technology," Azhar writes, "involves straddling two worlds" (p. 7).

It is precisely this two-worlds perspective that is missing from Han's work. As a consequence, his approach to digital technology seems closer to a consumer phenomenology. His work aptly describes how tech appears to someone scrolling mindlessly through their Insta feed. There may be some value in such a perspective on digital communication. But as an analysis of our predicament, and of digital technology, it runs the risk of mistaking an effect of societal problems for their cause.

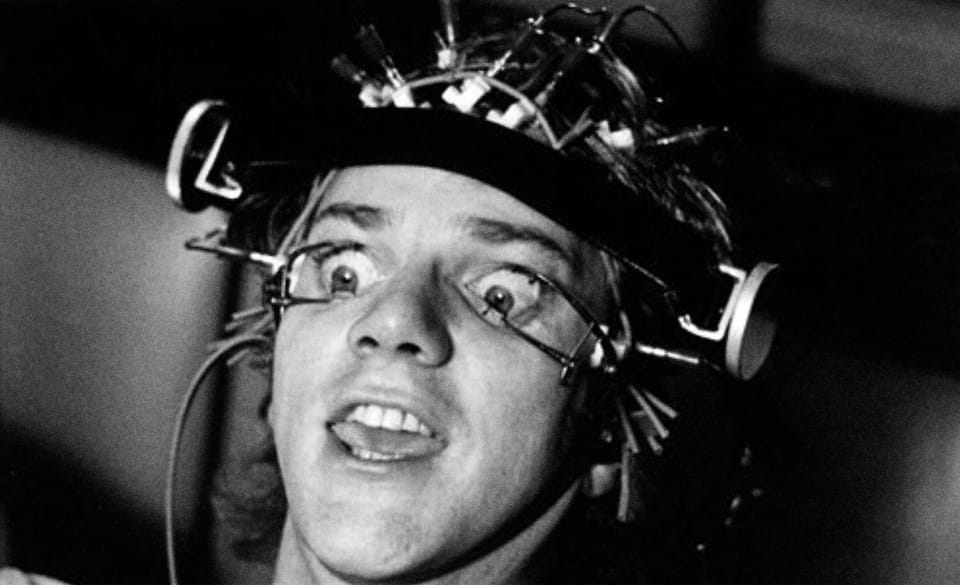

Still from Stanley Kubrick's film A Clockwork Orange (1971)

- If you want to read the passages I have in mind, a quick skim of Han's In the Swarm (2017, e.g. 1-3, 22-24), The disappearance of rituals (2020, e.g. 11-13), and Capitalism and the Death Drive (2021, e.g. 99-103) will suffice. ↩

- It may be that Han thinks that MacLuhan's work on mediality is enough to support this fusion of technical medium and neoliberal ideology, but I would not see any reason to accept the idea on that basis. That at best is true of specific social media like Facebook or Substack, which indeed seem to be designed to create the kind of digital panopticon Han describes. But to say this of, say, HTTP or the TCP/IP protocol would be as implausible as stretching McLuhan's thesis to link Christianity with ink. ↩