Reading Health Communism

In October 2022, Health Communism appeared, a book written by Beatrice Adler-Bolton and Artie Vierkant. It is an ambitious theoretical pamphlet. Its main ambition is to fuel the fight against capitalism, but with a twist. Consider, what shape should the fight against capital take? The authors reject the traditional Marxist proposal of reclaiming the means of production and initiate some kind of labour revolution. Instead, capitalism’s demise requires reclaiming health—a revolution of the ‘sick proletariat’.

The surplus

Capitalism depends on health, because capitalism needs workers. Yet, because of this dependency, capitalism has an interest in shaping what health is, who’s entitled to it, and how you can get it. Health becomes something individuals need to work and strive for. Capitalism sees those who don’t or can’t work and strive for health as second-rate citizens. The authors call this group the ‘surplus’ of capitalist society.

The idea of a surplus population is one of the two most central concept of the book. The idea stems from Marx and Engels, who used the term ‘surplus population’ for unemployed people living in destitution. But the authors expand this understanding. The surplus consists of all those populations who don’t actively generate a normal amount of economic value. The authors focus on disabled people, but prisoners and elderly belong to it too, and I think we should include children as well. Later on in the book populations of entire countries are diagnosed as being surplus, given colonialist economic forms of exploitation.

If we want to provide “all care for all people” (i.e. health communism), then we must begin by critiquing the political and economic role this ‘surplus’ population takes up in capitalism. The constructed division between workers and surplus must be broken down. It’s a pernicious division, because, as the authors claim, everyone is ill under capitalism.

Surplus populations are vulnerable, but their vulnerability is not due to their intrinsic condition (missing a limb, chronically ill, frail) but due to how the capitalist state has deliberately abandoned them—what Ruth Wilson Gilmore calls ‘organised abandonment’. Although in capitalist societies the surplus populations are portrayed as a drain and a burden, in fact they are a massive source of revenue. To be marked as surplus is also to be marked for economic extraction.

Extractive abandonment

This gets us to the second central concept of the book: extractive abandonment. The authors use the term to describe how capitalism has commodified disablement (but also incarceration, or elderly care, or colonial exploitation).

They build on Marta Russell’s work on the money model of disability: instead of thinking of disability as a medical condition, or a social condition, it is importantly an economic condition. Disability becomes an opportunity for public money to flow into corporate pockets. And the same holds for prisoners, or people in care homes, and developmental aid.

What the authors want to say about extractive abandonment is that it is vital to capitalism, and to the state. They write that it is how the state constructs itself and its political economy through optimising the population at a demographic level (read: eugenics).

From welfare to humanitarian extraction

Historically, the authors take their readers on a safari through developments in social care systems. We begin with a welfarist moment. The authors stage Otto von Bismarck, who just before the Second World War introduced the first social insurance system in Germany. You might think it’s friendly to offer factory labourers some protection against accidents and sickness. But the rationale of Von Bismarck’s system was first and foremost to stifle the emerging socialist movements. A pacifier.

The authors argue that Von Bismarck set the tone for all all modern health care reform, which has always been anti-revolutionary and about patching up the defects of capitalism. They show that even the labour movements contributed to this charade. What is distinctive of all versions of the welfare state is their ambivalent attitude towards the surplus. Yes, resources must be spent on them so as to rehabilitate them back into the labour force as quickly as possible, but they must also continue to suffer, so as to repel others who are thinking of relying on social care. Those people who cannot be rehabilitated need to be put in an asylum and taken away from society. Although we’ve officially abolished the asylum, the authors argue, there are now other institutions and structures that have taken its place.

The second moment in social care is exemplified by the World Bank’s 1993 World Development Report (“Investing in Health”), which defined a reshaping of the economy of health, from health as something social and shared, to health as something individual and a matter of individual behaviour. (In fact, this development has already been described by Robert Crawford in the 1980s, and he used the term ‘healthism’ to mark this shift.)

The report of the World Bank proposes a two-tiered system: public provisions are made for last resort health services, regular care is privatised. The result is that insurance companies focus on insuring against low-risk regular care, and try to push the responsibility for high-risk people (read: the surplus) towards the state, who will give them only a bare minimum. The authors see this as shift away from post-war colonial posturing towards a humanitarian-extractive economy of health.

Trade and intellectual property

It is here that I found one of the most interesting discussions of the book. The authors describe how the pharmaceutical industry was instrumental in fusing together intellectual property rights with international trade agreements (in the TRIPS agreement: Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights). This effectively excluded a large part of the world from being able to develop important drugs, and relegated entire countries to ‘surplus’ status – money can be extracted from them by selling the expensive drugs they need.

Prior to TRIPS, if someone else made your drugs in some far-away country, big pharmaceutical companies had to rely on local enforcement of intellectual property laws. But with TRIPS, such breaches of intellectual property law can be construed as violations of international trade agreements, allowing for political intervention with sanctions and threats of trade restrictions. The authors give examples of how TRIPS has stymied fair access to drugs in various countries. And not only the pharmaceutical industry has learnt to wield these economic-cum-political bludgeons, but the insurance industry as well. As a result, the ‘surplus’ countries are forced to set up every aspect of their health economies in such a way as to enable extractive abandonment by global capitalist enterprises.

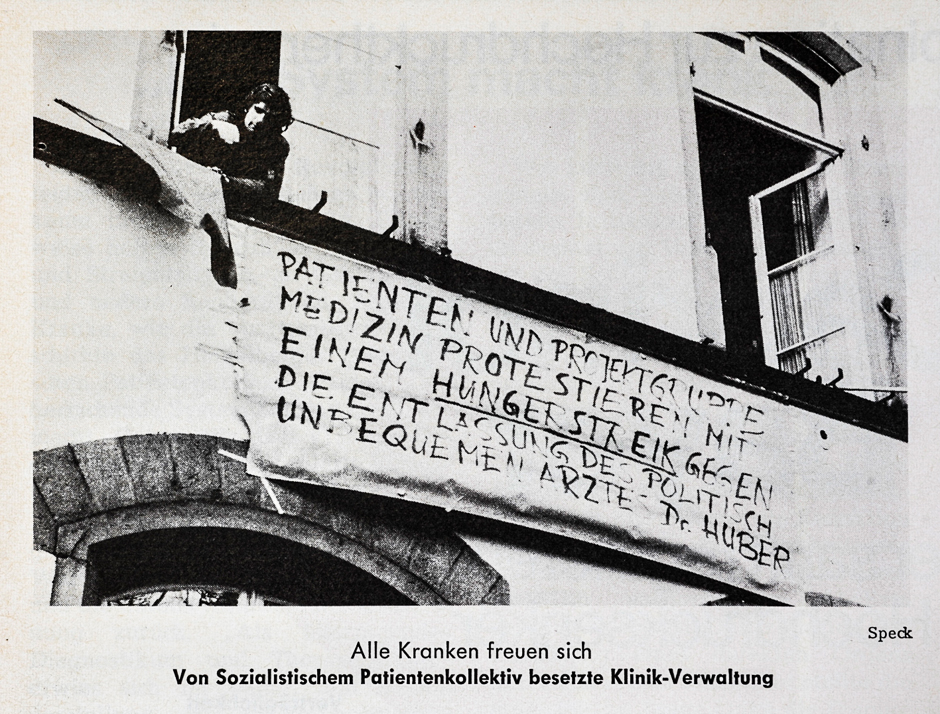

Socialist Patients’ Collective

The final two chapters of the book offer an account of the Socialistisches Patientenkollektiv (Socialist Patients’ Collective, or SPK), a movement that started in the 1970s in Heidelberg, Germany. The authors say that the project of SPK is “the closest direct ideological precursor” to what they call health communism.

In the background of SPK is the anti-psychiatry movement (which was instrumental in popularising the social model of mental illness), which typically stuck to offering institutional critique from the position of the doctor. SPK took a different strategy, dismantling the doctor/patient opposition, and trying a political form of treatment. Wolfgang Huber was the doctor who started these experiments together with patients. They were met with a hostile institutional response, with some hostility being medical, and some political and ideological.

In their 1972 manifesto Turn Illness into a Weapon SPK argued that medical science must be controlled by the sick, the people who need it, and they set up a People’s University to make a start with this. Because everyone is sick under capitalism, SPK celebrated illness as a revolutionary tool. The ‘sick proletariat’ must revolt. Here they saw treatment as a necessary step. But the treatment they developed took a radical, communitarian, and anti-capitalist form.

We must not forget here that SPK lasted less than two years, and never reached much more than a hundred members. It’s a small movement in a sea of post-1968 turmoil, and I find it hard to disentangle the authorities’ objections to SPK specifically and their objections to the broader counter-cultural and anti-capitalist tendencies of the 1960s and 1970s. Unfortunately, the authors of Health Communism seem to be too electrified by SPK to offer a clear and critical perspective. At points, the chapters about the movement read as a hagiography, with collections of justifying quotations stringed together in to paragraphs. That said, the message is clear: “Look, SPK got it right! They saw what was wrong, but no one believed them. Now it’s our turn to take up the baton.”

But a reader (well, this reader at least) is still left rather puzzled about what SPK actually did and thought. In these chapters I would have loved less theory and justification, and more history and biography. What did a day look like in the rooms of the SPK? (In a curious turn of events, they were given their own space in the Heidelberg university hospital to gather and practice.) What did they read or discuss? This would have helped to articulate the positive ideals of Health Communism better.

The host body

In conclusion, the authors say that they have shown how capitalism shapes health, and that it has shaped itself around health. In the shaping of health, capital has constructed a class division: the healthy workers on the one hand, and the ill and mad surplus populations on the other.

But if this is so, then what about the claim that everyone is ill under capitalism? Doesn’t that undermine the idea that capitalism constructed a division? I think that the authors want to say here that health is strictly speaking a fantasy or idealisation, and that the people who are classified as healthy in society are just those who are able or willing to uphold the fantasy. And there’s a point to this. I know nobody who isn’t anxious, fatigued, sore, broken, or ill. Yet many people would still go on to declare themselves healthy.

That we are all ill under capitalism, then, means first and foremost that we’re all surplus to capital. All of our bodies are being used for profit-making, and they show the signs of it.

The authors close their book by saying that “capital resides in health, as its host.” Here they use the metaphor of a parasite and its host to clarify how capital and health are linked. But the image is ambiguous: is capital the host, or health? Later they more explicitly say that health is capital’s host body. Following the imagery, that authors claim that capital can’t kill its host, or it would have nowhere to reside, and nothing to exploit. So the bold conclusion is that capitalism needs health, and that by reclaiming health we will bring down capitalism.

I think the authors mean that capitalism needs a social division between worker (i.e. health) and surplus (i.e. illness). Threaten that division, and you threaten capitalism. However, to argue for the claim that capitalism needs health, the authors have at best shown that—de facto—capitalism always has made these distinctions, be it in various ways. This is not enough to convince me that removing the distinctions will kill off capitalism. Capitalism is a many-headed beast, as we know all too well, and I just have a hard time believing anyone who claims to have discovered its Achilles heel.

Whether Adler-Bolton and Vierkant’s bold conclusion holds true doesn’t really matter. As a slogan it sounds good enough. But practically, the interesting take-home message of the book is that health is “imbricated” in capitalism (a word meaning ‘overlap’; the authors love to use it). I would say that health and capital are ‘entangled’. This means we can’t trust capitalism to take care of us, because the very system of ‘taking care’ has always already been set up with an eye on extracting profit, and this requires people to stay sick. A move towards health communism, towards all care for all people, is a move towards liberating care from this extractive economic system.