What could post-collapse computing be?

Microchips are some of the most extraordinary objects humanity has ever made. This writes John Lanchester in the first March issue of the London Review of Books, which I read during breakfast. Computer chips are extraordinary in part because they seem impossible to put together. This fact about them makes chips dangerously fragile technology, and it is not obvious that we can continue to rely on them when the full effects of climate change will have made themselves felt.

Exceptionally fragile

In 1961, the first chip had only four transistors. But sixty years later high-end chips like those designed by Apple or Huawei cram ten or twenty billion transistors in a piece of silicon not even half the size of a postage stamp. The size of transistors is now measured in double or even single digit nanometres.

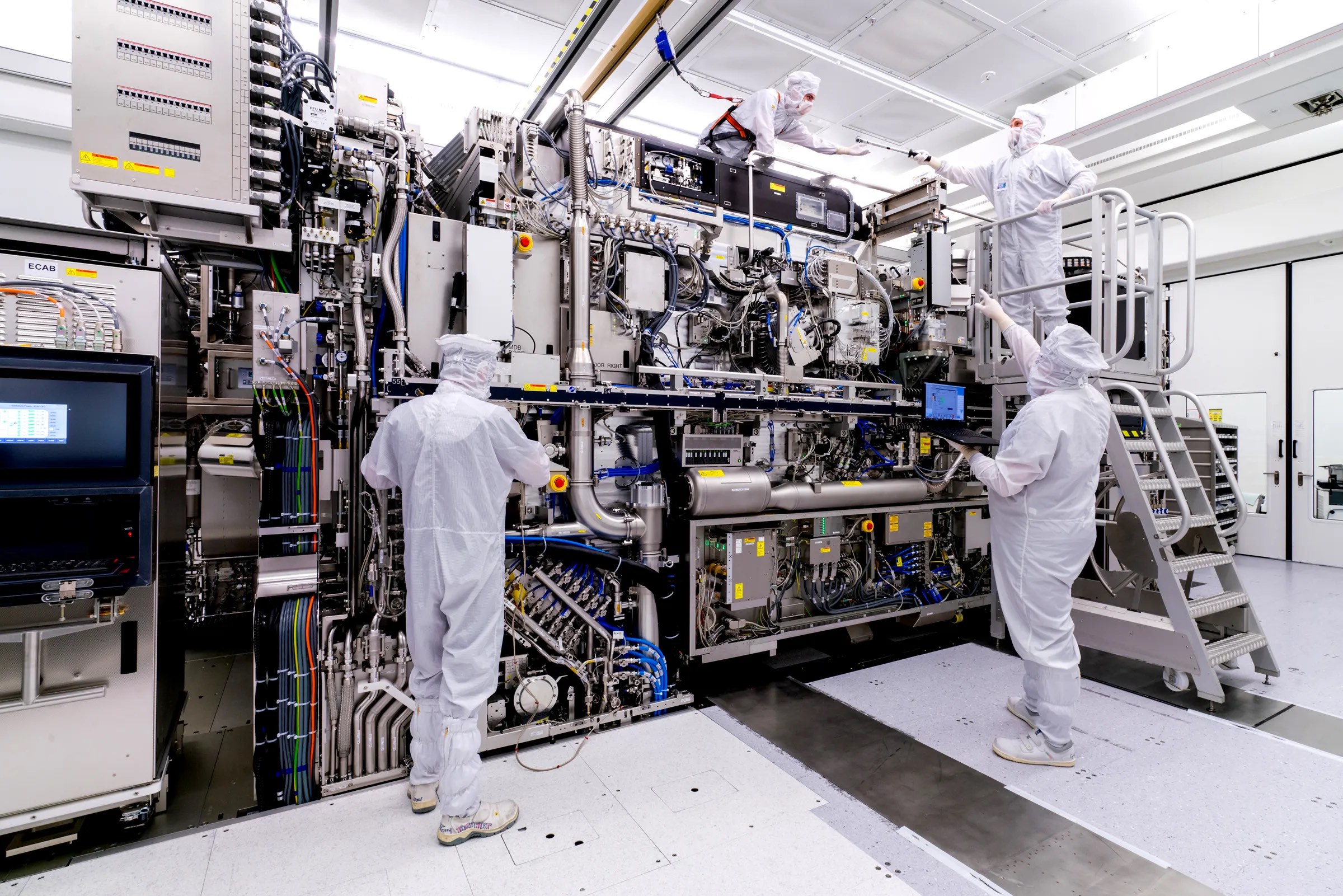

To etch the circuitry in between the molecules of silicon wafers, chip manufacturers use photolithography with extra-ultraviolet (EUV) light. Many insiders thought for a long time this process was technologically unfeasible. They were wrong, but only just. EUV photolithography requires such specialisation that there currently is only one company in the world that can assemble the machines to make the high-end chips that power your iPhone or new laptop, and only one company that knows how to use those machines in a production line to make those chips.

Lanchester's claim that microchips are extraordinary artefacts is based on Chris Miller's book Chip War (2022). Miller is an historian doing research on key shifts in technology, international politics and economics. This recent book of his offers a history of the development and manufacture of semiconductors and integrated circuits, better known as chips. Not only are the chips themselves exceptional, but so is the chain of dependencies that underlies their manufacture.

The world's production of advanced computer chips relies crucially on only a handful of companies. The machines to etch the nano-sized circuitry onto those chips are designed and assembled by ASML in The Netherlands. And the facility that actually produces the chips themselves is TSMC in Taiwan. There are a few companies that supply the components necessary for this process, such as lenses, lasers, and ultra-pure silicon, and a few facilities that are capable of producing less sophisticated---but still sophisticated---chips. There are no other producers. No one else can pull off this technological feat. In other words, a dominant engine behind current society rests entirely on an exceptionally thin supply chain.

When China succeeds

Miller has only so much time to marvel at the feat of technology. His main concern is with how microchips have changed almost everything we do and almost every tool we use, and how more and more our lives depend on them. Because this gives whoever produces chips immense power. This is why current geopolitics so often pivots around the semiconductor industry. The 'chip war' is a key determinant of what is happening in world politics right now.

In his book Miller frames it as a war between the US and China. Currently, China is largely dependent on importing advanced microchips from suppliers that are in one way or other controlled by the United States. The quite understandable ambition of China is to set up its own production facilities, so as to reduce its economic and political dependency on other countries, the US in particular. If China succeeds---when China succeeds, because in my mind there's little doubt that they will---it would likely mean economic superiority and the end of the global hegemony of the United States. It would take away from the US one of the key industries its economy and military relies on.

The dynamic Miller describes in his book made a lot of the details of current geopolitics fall into place for me. I now see better why suspicion of the Chinese tech giant Huawei needed to be roused in recent years. Why TikTok suddenly is a problem (and Facebook still isn't). Or why the US is pushing The Netherlands to make it illegal for ASML to sell its advanced photolithographic machines to China. And it explains for a large part why the US is so keen on defending Taiwan, and why military force would potentially be worth it for them.

What if chip manufacturing grinds to a halt?

But there is another thing that's good to notice about this portrait of the microchip. Chips have become integrated in almost every part of our lives. Computers, telecommunication equipment, cameras, kitchen appliances, research labs, libraries, maps, manuals, encyclopedias... all these things now depend on advanced microprocessing technology. Even further, as I've described before, we more and more outsource even our own cognitive processes to the 'artificial intelligence' that is currently developed. If there's no AI without piles and piles of microchips, then soon there may be no significant human thinking without a steady supply of chips either.

What happens if chip manufacturing suddenly grinds to a halt? Given the fragility of the supply chain, this is not a far-fetched possibility. A powerful earthquake near TSMC in Taiwan, for example, would likely shut down global production for months if not longer. Miller estimates the costs of such an event would be measured in the trillions of dollars.

Societal collapse is no longer a 'doomer' prospect

But earthquakes are one-of events. There's a more serious contingency on the horizon. What happens if humanity is forced to transition to forms of society that are unable to sustain such complex and resource-demanding production processes?

In their book Deep Adaptation, Jem Bendell and Rupert Read write that climate change "will probably, or inevitably, lead to the collapse of industrial consumer societies." They think that, apart from trying to reduce emissions and pollution, people urgently need to plan for a post-collapse world. In such a world, many things that we now take for granted will have to be given up because they can no longer be sustained, either because of lack of resources, lack of power, or lack of people.

Though their view has been portrayed as 'doomer' or 'alarmist', the idea that society as we know it won't survive this century is rapidly becoming mainstream. In 2020, a group of hundreds of scientists wrote an open letter to the world, warning that "researchers in many areas now consider societal collapse to be a credible scenario this century". The most recent IPCC report projects a global warming well over the 3C rise that a recent report by The Economist marks as 'catastrophic' and 'disastrous' if it happened. But it will happen. Sustainability analyst Gaya Herrington calculated that collapse may happen as soon as 2040. This is reality catching up with half a century of lobby-driven optimism.

Of course, the collapse predicted here won't be a single event. That's how a disaster film would portray it no doubt. But in fact it will be an extended chaos of processes, covering a spectrum of deterioration and decay. Many of the things people now take for granted they will lose: unconcerned holidays, exotic fruits and produce, accessible health care, insurance, housing, and who knows what else.

Preparing for post-collapse computing

Let's accept that this is really happening. Then we should see that one thing at risk is computing and digital communication. The supply chains of the chip industry are fragile due to the extreme complexity of the product. Only very few sites are capable of producing sophisticated microchips. Miller mocks Mao Zedong's future vision in which (in Millers interpretation) all people will make semiconductors---"as if every member of the Chinese proletariat could forge chips at home" (385). Whether it truly was Mao's or not, as a vision this is unrealistic precisely because the manufacturing of a chip requires an unfathomable range of resources and tools. There is no way the semiconductor industry can become 'small' or 'local'.

This is why it should become a key priority to prepare for post-collapse computing. What could post-collapse computing be? Well, I think we better take that question extremely seriously. Climate change is likely to force far-reaching changes upon the way people use and rely on computers. In particular, I think societies should prepare themselves for a situation in which people are no longer able to produce their most extraordinary object. The thin connections that run between key nodes of the semiconductor industry are probably too fragile to withstand an era of natural disaster and war, of rationing of energy and resources, of widespread famine, of international suspicion, and of unprecedented migration away from coastal areas and newly forming deserts. In such a world, chip manufacturing is likely to be reduced to a trickle at best.

How would we manage? Not, I think, by simply letting go of computers. Tragic as it may seem, humanity can no longer do without advanced computing. Societies have become too complex, and people have grown too dependent on a technology that in many ways is an ideal solution to complexity. Just think about it for a minute. In what ways is your daily activity already scaffolded by the network of computers that surrounds you, near or far away? For myself I can easily give dozens of examples.

Chips as relics of the old days

Increasingly often the scaffolds offered by high-tech computing are essential to keep you going. There are already plenty of things most people can no longer do without a computer: communication over distance, keeping accounts, banking, writing novels or articles, looking up information, navigation... And at least in the coming years this list will continue to grow at increasing speed, because it is the front line of capitalist expansion.

What would happen to all such essential tools if the chip factories are on fire, under water, or when their workers are dead or starving? In a post-collapse world, we may find ourselves reliant on computer technology left over from 'the old days'. Would that be feasible? Is the technology we now design resilient enough to last that long? Easy enough to repair? Would it be enough to sustain a low-tech internet?

It is hard to predict the future, but it is good to be prepared. And preparing for post-collapse computing may require us to alter current designs and manufacturing processes with an eye on making microchips more sustainable and durable. In forty years time, the microchips that are rolling down the assembly belt as we speak may well come to be cherished as precious relics, carefully kept and maintained to power essential aspects of life. Connected to solar panels, wind turbines, or some other improvised energy source, they could then have obtained a status as elusively complex devices, extraordinary objects powering improvised peripherals that are much less technologically sophisticated.