Thinking as a Service

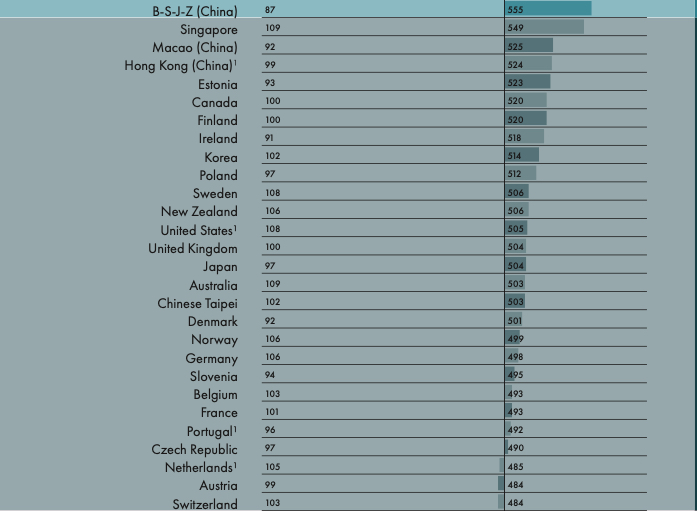

In several wealthy countries basic literacy is declining year on year. Here I want to focus on The Netherlands, a country I understand well. In the most recent PISA report, which looked at data from 2018, The Netherlands performed poorly given its wealth, trailing a large distance behind Estonia, Singapore, and China.

The report was no surprise. The Dutch Education Council has tried to raise awareness of this decline for years, yet there is no sign anything significant is happening to counter it. Why aren't we seeing a more concerted effort to invest in and improve primary and secondary education?

For, surely, it matters a lot. Reading skills involve more than the ability to reproduce a text; they demand comprehension as well. Indeed, the PISA score measured precisely comprehension, "the capacity to understand, use and reflect on written texts in order to achieve goals, develop knowledge and potential, and participate in society".

Someone who struggles with reading is likely to struggle with writing as well. And indeed, also when we look at the ability to write, the majority of Dutch children leaves primary school with writing skills that fall below the desirable threshold. In fact, a quarter of school-leavers does not even possess the most basic level of writerly competency.

Anyone who is familiar with Dutch society should already be able to spot the effects of this steady decline on everyday life in the Low Countries.

Cognitive deskilling

Needless to say, this is not the fault of children. I think it is fairly uncontroversial to see the decline in literacy and comprehension as a systemic failing, a result of how society at large has ceased to value the ability to read, write, and to reflect and understand. (Consider, it's not only children that read worse---their parents do so too.)

In this light, I think it's crucial to see these declines against the backdrop of a much bigger picture, one that extends well beyond the specifics of the education system. Where is society heading?

The answer is: towards a de-skilled society. More and more, thinking itself is being turned into a service, a product that is offered by some company or other. When people look for answers or want to understand something, they turn to Google, Bing, or to social media. There, they are likely to find easily digestible, byte-sized snippets that will do for most practical purposes. Consultancy, instead of being a specialist service, has become a mainstream staple.

Examples are everywhere to find. Instead of reading a manual, people will find the solution to a problem with their laptop or dishwasher as a 'top hit' on a search engine. Instead of reading a news article or analysis piece, people will base their view of what's happening on the gist distilled for social media. More and more do we rely on auto-completion of emails, and on automatically generated messages and choices. This outsourcing of thinking happens in scientific contexts as well, and with the advent of 'Artificial Intelligence', all of this increasingly takes place cheaply and automatically, without meaningful human intervention or control.

What I expect to see more and more is that thinking will become a service. A service to which you'll have to subscribe, either by paying with money or with your data. This Thinking as a Service model (TaaS) has been set in motion a long time ago, but I think we are only now beginning to see exactly how corrosive it is. It thrives on and promotes a specific kind of cognitive deskilling. As any other form of market-driven deskilling (think of what happened to cooking, exercise, repairing, cycling, networking, organising, etc.), the decline in reading and comprehension skills is a welcome and expanding opportunity for turning created demand into profit.

The true causes of literacy decline

With this in mind, it comes as no surprise that Google is increasingly infiltrating the classroom, or that people are imagining a life in which ChatGPT takes care of your emails and administration. When we worry about declining literacy in societies that should very well be able to afford decent education, we should not look too narrowly when we look for causes. Instead, as always, we do well to follow the money. The less capable people are to read, write, and understand, the easier it will be to exploit their helplessness for profit.