Why am I still on Twitter?

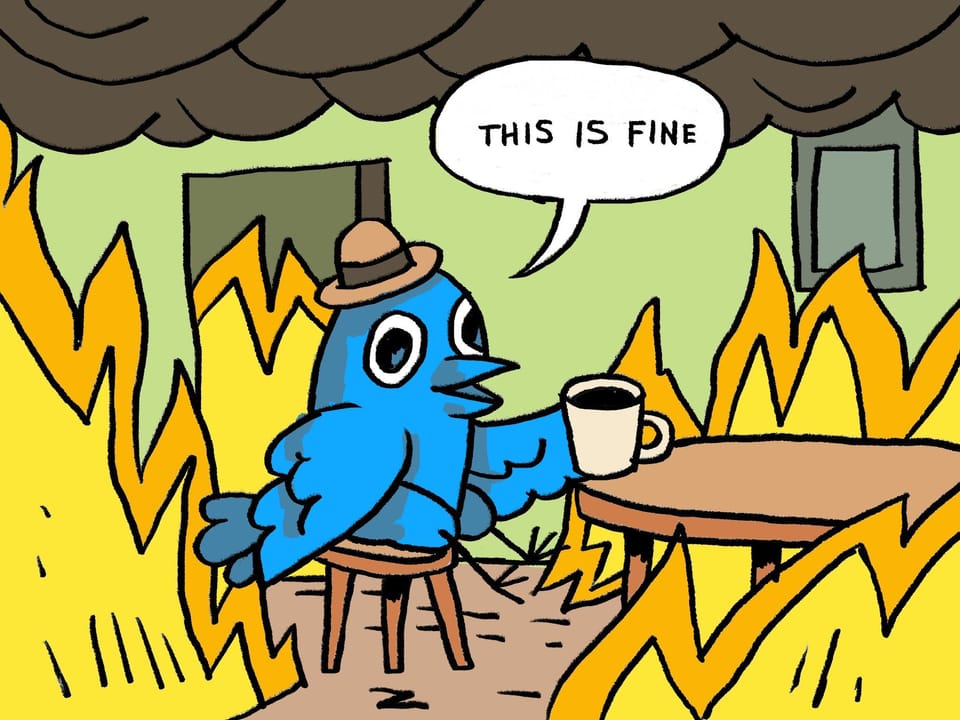

I sent my first tweet on the 17th of June 2009. It contained a six-word description of that afternoon—I was travelling somewhere. Back then Twitter was for me a way of finding out what my friends were up to. Now, twelve-and-a-half thousand tweets and fourteen years later, the experience of being on Twitter resembles that of standing in the lurid departure hall of a noisy international airport—an activity I would undertake only because I wanted to get somewhere, not because I particularly like it.

So, where do I want to go to? Why am I still on Twitter?

A bizarre and amorphous soup

I now use Twitter really only for two purposes. The first is information gathering. I keep hearing the same from many people. This bizarre and amorphous soup of searchable tweets is an almost unparalleled source of raw data. Its consumers include journalists who want to follow events, scientists who follow research that their colleagues are doing, and me. As Jessica Wildfire writes in a recent essay, "if you’re like me, you’re not on social media to watch cat videos. You’re not there for dopamine hits, one way or the other. You’re there for information."

If you know what you're doing---a big if, admittedly---then by sifting through piles of unfiltered junk you are often able to form a picture of what is happening that is more accurate and ahead of the curve. Annoying as may be, Twitter, pinnacle of tech venture capitalism, remains a central window on the world.

It's hard to overstate its value in this regard. The need for raw information is urgent now society has settled on wilful ignorance as a solution to several massive problems. Those invested in a malignantly growing economy firmly control the popular narrative. Thereby they shape the values and expectations of most people. It leads to a situation where the seriousness of many threats is downplayed or ignored, simply because they don't immediately jeopardise the economy. The messaging about COVID is a good example of this---an incoherent mixture of denial and downplaying, designed to repress that large numbers of people are dying or becoming disabled due to a preventable disease. Much the same goes for the climate disaster, which already ravages your society or will soon enough do so, but still gets illustrated with pictures of people lying on a beach. More generally, talking about the damage capitalism does to health, communities, ecosystems, and the human psyche is more or less taboo.

Warding off hordes of trolls

There's another reason I'm still on Twitter, and it ties in with the wilful ignorance I see around me. It is 'activism'. Or at least this is how I keep calling it to myself. This is the attempt of offering counternarratives that are more truthful and honest about the state of the world. The Twitter activism I have in mind tries speak to people who recognise the need for better and more social ways of living. It is the thankless task of reminding everyone that there is power in community; that sticking together and helping each other is the path to resistance. Increasingly this means warding off hordes of disingenuous trolls and the grunt forces of bot armies.

How that is going? Rubbish, to be honest. Plenty of commotion, but little progress.

Activism on social media platforms quickly hits a brick wall. At least this is my experience on Twitter. Yes, because so many people use Twitter for information gathering it is a good medium for raising awareness of problems and injustice. In some circumstances, social platforms like Twitter may even be your only way to communicate freely. And you could argue that such platforms are good for combatting the induced forgetfulness that we see everywhere.

But awareness does not equal action. It is one thing to understand the world, it is another thing to change it. You could even make this into a philosophical point, about what understanding the world amounts to. If you don't know how to make the world better, then how can you still profess to understand it?

Discourse as an end in itself

It is due to this gap between awareness and action that a platform like Twitter may well have a stifling effect. In her work on communicative capitalism, Jodi Dean has drawn attention to the fact that in the current internet economy, politics is more and more reduced to a universe of communicative acts, to speaking and saying and exposing, and explaining. The result is that we're prone to overestimate the political significance of communication, especially if it is part of an endless cacophony of messages.

I have noticed this in myself. Here's a typical example. I see you've tweeted, and I realise that it contains a key political observation. Perhaps you manage to put your finger on a important problem, or perhaps you draw attention to some overlooked form of injustice. Important problems need solutions, and injustice needs to be fought. For this reason, sharing your message among my followers by retweeting it tends to give me the satisfaction of having done a good deed. As if by spreading the word I have already moved closer towards solving the problem, have made a start with combatting injustice.

But have I, really? If recent experience is any guide, it is plain that people are all too capable of sitting on their awareness or knowledge, not doing anything with it besides, perhaps, spreading the word. The same holds for many of the bits I myself write and post. As an author it is easy to overestimate your contribution. In the end, it's just more words, right?

Now don't get me wrong, I do believe that there is a need for words. Words are crucial in offering new ways of thinking, and improving the world requires new ways of thinking. Words also have their part to play in raising awareness of problems, and such awareness is essential for people to be motivated to act. That's why I write. But I worry that on platforms like Twitter the words and messages have become increasingly detached from the actions. That is Dean's point about the current internet economy: it reduces politics to discourse. Discourse in and of itself is politically impotent.

What we direly need is resistance, organised movements, and social struggle. Discourse may be essential to get there, but it should never become an end in itself. Networks like Twitter promote the idea of discourse as an end in itself.

Post or vanish!

But that's not all. Social media platforms like Twitter have a stifling effect on political activism also because they expend valuable energy.

A disproportionate amount of energy is required merely to keep the communication channel open. This is much worse now than it was even five years ago. A friend of mine recently illustrated this well. 'In order to stay afloat in social media you have to post so much content,' he wrote. 'It’s too much. It’s overwhelming.' My friend is a synthpop musician working in Berlin. As so many artists, he relies on social media to share his work. Merely to break through the noise on those platforms, you need to nurture your feeds incessantly. For him that means posting on TikTok three times a day, six times on Instagram, and either a short or a long video on YouTube. Otherwise you'll vanish. And he's not even trying to cultivate a podium on Twitter, where maintaining a sizeable reach for many requires posting ten or twenty times a day.

What holds for art holds for online activism just as much. On Twitter, a lot of your time goes towards making sure the platform retains its status as a bizarre and amorphous soup of searchable tweets. Doing that is not activism. It is capitalist production work. It is free labour we're doing for one of the richest people in the world. My point here is not that this business model is inherently wrong (though I think it is). My point is that, from an activist perspective, this is time wasted. Heaps and heaps of time if you add it all up. Time we could have spent consolidating all those snippets of awareness and understanding into a politically lasting alternative.

The double bind of social media

Of course, now you want to hear what I think the solution is. It may seem that the easy way out is just to ditch social media. But is it? Should people fighting for justice and equality just abandon social media?

I don't think this is a good strategy. This is because social media are no longer frivolous, but they have become integral to the infrastructure of communication. It is a fact that many traditional forms of communicating have been replaced wholesale by online messaging. Many people read books online, or listen to their audio versions on Audible or some other platform. They read social analysis on Substack, Twitter, or Facebook. Reading a physical newspaper has become a quaint luxury. Whether we like it or not, social media may well be one of the best channels activists have for getting their messages out.

Dean acknowledges that social media have taken on this central role in communication. "Practically speaking then," she writes, "we have to be dialectical and recognize that it is going to have a good side and a bad side." The good side is that they allow us to communicate. The bad side is that they prevent us from actually doing something. As she continues, "the more people focus on the internet and network communication as the important thing, the less they focus on building a revolutionary party capable of forwarding a revolutionary movement and having some kind of plan for what happens afterward."

Controlling networks and communication

Acknowledging this fundamental ambivalence of social media is important. But I think Dean's work risks a false opposition. She regards a focus on the internet and network communication as being in tension with building a revolutionary party. But I do not think the two are necessarily opposed.

I think that building a revolutionary party—a party capable of launching a revolutionary movement, a political current that has formed a joint vision for what should happen afterwards—that building such an organisation may well require a firm control over parts of the internet and network communication. This is because the internet and its networks have become a default communication channel in most societies. With the exception of face-to-face conversation, it is what people use. Trying to build a social movement bypassing the internet may work in very localised settings, but I'm afraid it won't get you very far.

Instead, we should see the ambivalence of social media as part of social struggle. We need to learn to use the internet in our favour. A big part of the problem is that activists on social media platforms like Twitter do not control their own networks. They do not control the communication channels they rely on for building a solidary movement. This is extremely risky, as it leads to a situation in which the movements we build will be tethered to the capitalist forces they're trying to get rid of. Communication will have to play by the rules of Twitter and the likes, which means it is likely to remain stuck at the level of sharing fragmentary snippets of awareness and understanding.

If part of the problem is a lack of control of networks and communication channels, then part of the solution is to gain that control. Instead of spending an hour reinforcing the power of some of the richest people in the world, everyone who wants to help further socialism would do well to invest that hour in building communication channels that actually will help socialism grow stronger. Just as socialist movements in different historical and material circumstances had to learn to form networks, we today have to learn. We have to learn to form networks that encourage genuine learning and discussion of what world we want to build, instead of encouraging the proliferation of like-bait and spectacle.

A failure of imagination

How all of this will look concretely? It's too early to tell. My experience on the Fediverse using Mastodon so far has been good, but I notice I need to unlearn habits of passive interaction and try to team up with friends and comrades much more. Perhaps we have to try to slow down our speech, and move to asynchronous discussion in magazines and newspapers set up to help us to achieve what we want. The part for commercial platforms like Twitter in all this should at best be peripheral, for the simple fact that they're a huge liability and waste of time.

In Capitalist Realism Mark Fisher wrote that currently it seems impossible to imagine alternatives to capitalism. I think this holds true for the capitalist internet economy just as much. It is hard to imagine an internet and online networks that actively promote and cultivate resistance, organised movements, and social struggle. But the impossibility Fisher describes is not logical, it is historical. And as such it is subject to change. It is a failure of imagination, not a limit. And where you fail, you must try harder.